Automatic Data Enumeration for Fast Collections

This post is based on a paper of the same name, published at CGO 2026.

Data collections are everywhere! They provide a powerful abstraction to organize data, simplifying software development and maintenance. However, choosing how we implement each collection in our program is critical for both performance and memory usage.

While general-purpose data collections (the ones in the C++ STL, Abseil, etc.) provide drop-in replacements for quick performance tuning, the real value comes from specialized implementations. Specialized implementations (bitsets, prefix trees, bloom filters) provide superior performance and memory usage compared to their general-purpose counterparts. However, they require additional constraints on the kind of data stored, and the methods used to access them.

For example, let's look at bitsets. In this domain, other implementations pale in comparison, as shown in the speedup table below. However, a bitset requires dense (or better yet, contiguous), integer keys.

| Implementation | Insert | Remove | Union |

|---|---|---|---|

std::unordered_set |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

absl::flat_hash_set |

1.61 | 0.40 | 1.71 |

boost::dynamic_bitset |

9.08 | 1.24 | 5817.38 |

Those are some pretty nice performance boosts, and if my set is dense enough we'll get good memory savings too. But, what if I'm in a domain that doesn't have the necessary guarantees to use a bitset? Is there any hope for the folks processing non-integer data types, or sparse domains?

The good news: There is.

The bad news: It's not free.

Data Enumeration

If we don't have inherent data properties guaranteed by our domain to rely on, we can instead engineer the desired property.

Take the following code, which iterates over a list of strings (items) and prints unique items by tracking duplicates in a set (seen).

items = ["foo", "bar", "foo"]

seen = set()

for item in items:

if not seen.has(item):

seen.insert(item)

print(item)If we want to use a bitset instead of a set, we can do a bit of transformation (shown below).

First, we'll assign unique identifiers to each item and maintain a bidirectional mapping (enc and dec) to convert between the ID and the actual data.

Then, we convert the data stored in our input array to use IDs (items).

Now that we are iterating over IDs (which we've assigned to be contiguous), we can convert seen into a bitset.

Finally, we need to patch up any use that requires the original (the print statement) by decoding the identifier.

Et voilà!

enc = {"foo": 0, "bar": 1}

dec = ["foo", "bar"]

items = [0, 1, 0]

seen = bitset()

for i in items:

if not seen.has(i):

seen.insert(i)

item = dec[i]

print(item)We've successfully converted our program to use a bitset, instead of a set. Now, we can reap the performance and memory benefits! Additionally, we can perform comparisons between our items much faster by using their ID instead of the string.

However, we've gotten ourselves into a bit of a pickle now by applying this manually.

I have to juggle my IDs and values everywhere in the program.

Additionally, I need to make enc and dec available anywhere that I need to translate between IDs and values.

Furthermore, I'm left with a bit of a performance headache figuring out if I should use IDs or values in different parts of my program.

Yeesh, this sounds like the job for a compiler!

Automatic Data Enumeration

Instead of performing data enumeration manually, I propose that we do it automatically. Looking at the example above, the transformation itself is rather mechanical. We just need the proper substrate to implement it. LLVM is a bit too low-level, and there's no existing MLIR dialect for this stuff, but I've heard of a cool new compiler IR on the block: MEMOIR!

MEMOIR is nice here because it preserves high-level semantics about data collections, which we'll need to transform how we store our data. Additionally, its SSA form makes the analysis we need very easy. Sounds like the perfect substrate to implement Automatic Data Enumeration (ADE). I won't get into all the nitty gritty about how we mechanize the data enumeration transformation here, but I will give the high-level overview.

Fundamentally, ADE transforms the program to build an on-the-fly enumeration (the bidirectional mapping from IDs to values). This means that whenever you encode a value for the first time, it will be assigned a unique identifier. ADE is responsible for determining where we should use IDs instead of values, and then inserting translations using the enumeration. As you would expect, this introduces a lot of redundant translations, which can be eliminated:

enum_A = ...

seen = bitset()

for item in items:

id_1 = enc(enum_A, item)

if not seen.has(id_1):

id_2 = enc(enum_A, item) # redundant, replace id_2 with id_1

seen.insert(id_2)Eliminating redundant translations is the main performance driver of ADE, so we introduce a few transformations that introduces more redundancy. One of these is sharing (shown below), where we have two sets share the same enumeration. Sharing has the added benefit of amortizing the cost of constructing the enumeration.

enum_A = ...

seen = bitset()

seen_twice = bitset()

for item in items:

id_1 = enc(enum_A, item)

id_2 = enc(enum_A, item) # redundant, replace id_2 with id_1

if not seen.has(id_1):

seen.insert(id_1)

elif not seen_twice.has(id_2):

id_3 = enc(enum_A, item)

seen_twice.insert(id_3) # redundant, replace id_3 with id_1

There are more optimization, with full details available in Section 3 of the paper.

Evaluation

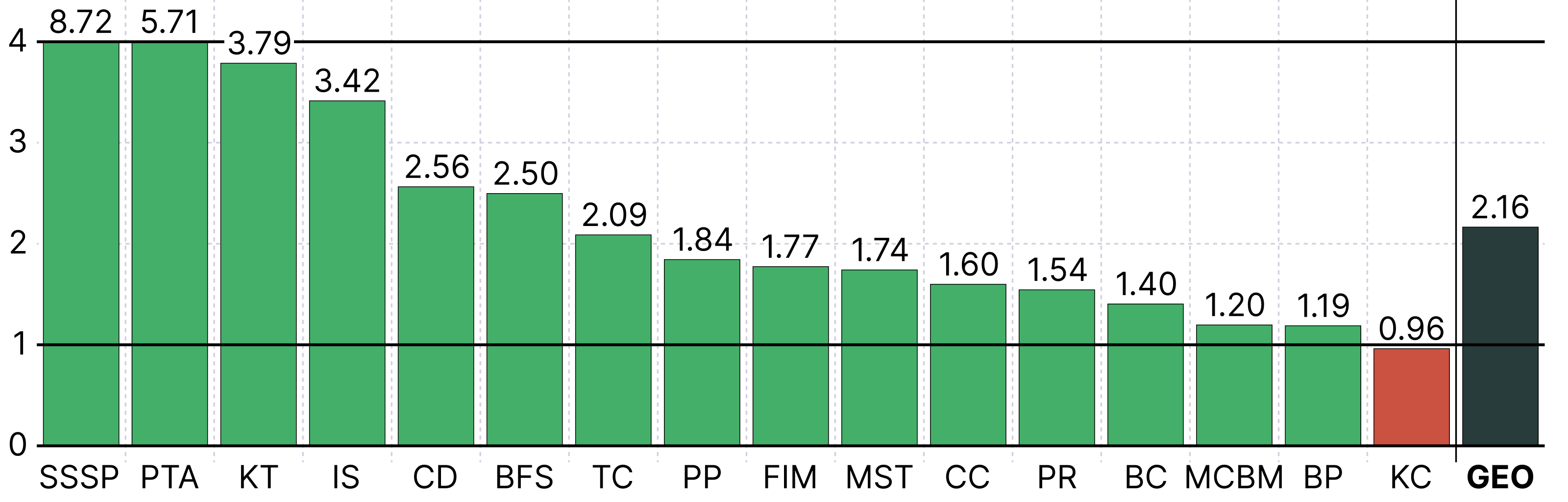

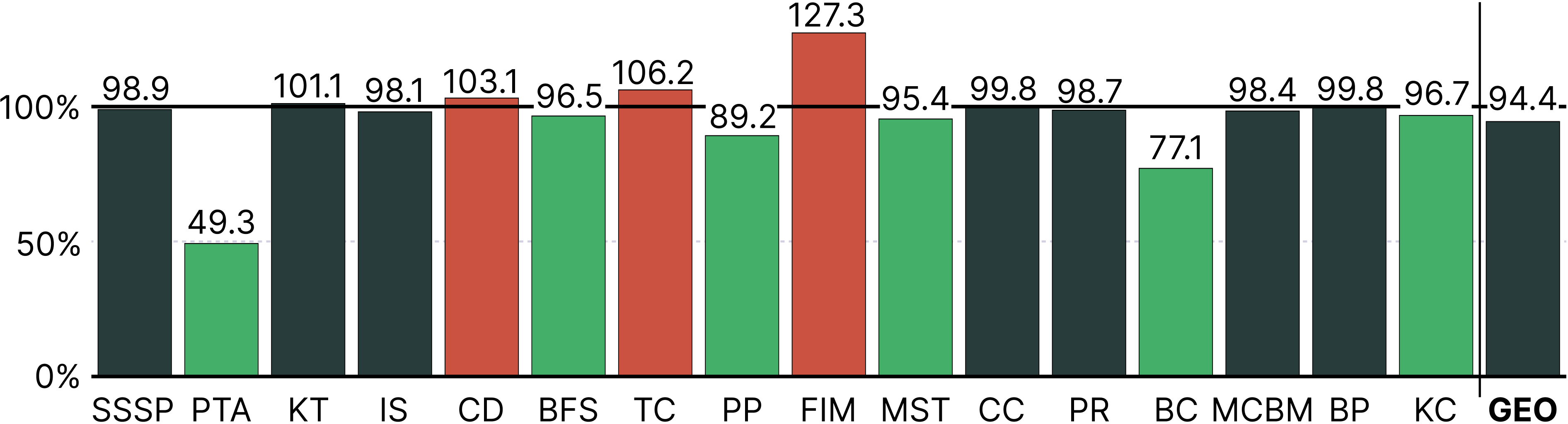

So that's all great, but how about the performance? In short, ADE provides significant performance improvements in the majority of our benchmarks. While ADE incurs an increase in memory usage for a few cases, we find that the majority of benchmarks experience no memory explosion, with some seeing significant memory savings! For a more detailed evaluation on both Intel and ARM machines, along with comparisons to Abseil swiss tables, see Section 5 of the paper.

Tuning

In addition to fully automatic ADE, we provide ways for users to guide the optimization. This lets you enable/disable enumeration for a collection, and prevent/force sharing between collections. By overriding the static cost model, users can fine tune data enumeration for their specific application.

We did a brief case study for LLVM Andersen-style points-to analysis (PTA). In short, we identified a case where sharing with a specific collection was detrimental to performance. The full details and exploration are in Section 5, RQ4 of the paper.

By injecting a single noshare directive, ADE achieved a speedup of 78x (13.7x over fully automatic ADE).

In addition to the performance gains, memory usage (max resident set size) was reduced by 71% (compared to 49% reduction with fully automatic ADE).

Conclusion

Automatic Data Enumeration provides a fully automatic, transparent solution to one class of memory optimization in the compiler. With ADE we are able to achieve significant performance improvements without the need for developer input, though tuning can unlock further savings. Thanks to MEMOIR, the implementation is straightforward (and fun!). I believe that data enumeration is just one of many memory optimizations that can be automated by the compiler, and I hope for a future where developers can trust the compiler to handle most of them.

Further Reading

For more information, see the paper:

@inproceedings{MEMOIR-ADE:McMichen_Campanoni:2026,

title={Automatic Data Enumeration for Fast Collections},

authors={McMichen, Tommy and Campanoni, Simone},

booktitle={CGO},

year={2026},

}To see how we implemented ADE in the MEMOIR compiler, see the open-source repository.